Your cart is currently empty!

Semantic Conditioning

in the Ersatz Academy

One of the main questions raised by The Ersatz Academy’s ‘re-education’ techniques is whether the manipulation of words and their sounds can affect human behavior under certain conditions. Slogans, such as Lawson made liberal use of, are characterized by obvious audible techniques such as rhythm, rhyme, repetition, and three types of parachesis (repeated similar sounds): alliteration (initial sounds), assonance (vowels), and consonance (consonants). Homonyms are also used to confuse or encourage different interpretations. These devices are also often found in advertising (Xiaosong; Foster; Dingfelder, 2012) and have been exploited throughout history in political propaganda (Wikipedia: Alliteration).

The methodology of Wordswright’s AI is loosely based on originally Russian research, later referred to as semantic conditioning by Gregory Razran in 1939. It refers to the conditioning of a natural reaction to the meaning of a word or a sentence. In such a training procedure a certain physical response is stimulated repeatedly while being paired with a key word – until an association develops between the two. For instance, salivation is stimulated by chewing gum while a word is pronounced until the same salivation response is stimulated by the word alone, without the gum.

In follow-up research reviewed by Razran (1961), both synonyms and homophones of the original words were used as the conditioned stimuli. In such experiments involving alert subjects, synonyms generally resulted in similar responses, whereas homophones did so to a lesser extent. However, when the brain cortex was inhibited in some way (e.g., through a drug causing drowsiness) homophones became more effective than the synonyms in stimulating the same response.

For instance, Schwarz (1948) conducted an experiment in which subjects were conditioned to associate a sudden flash of light with a particular word. Under normal circumstances, the subjects demonstrated the same response (increased pupil sensitivity) to different words with similar meanings, but not to similar-sounding words with different meanings. However, when they were under the depressant influence of chloral hydrate, they demonstrated the same reaction to words that sounded similar, i.e., to homophones but not to the synonyms.

So, it appears that the stressed brain – whether through fatigue or induced drowsiness, young age, low IQ, or other disturbances of the general condition of subjects (e.g., headache, influenza) – becomes more susceptible to being confused by words that have similar sounds but different meanings. That is, it’s plausible that under certain conditions, people become more suggestible: they may tend to believe and follow phrasing that makes it appear that the words make logical sense together simply because they sound similar.

One of the aims of using the AI mentioned by the Stranger was to induce such a compromised state of mind in order to amplify the effect of slogans that combine similar sounding words.

Here is a more complete review of this research on semantic conditioning.

Slogans in which complex issues are “compressed into brief, highly reductive, definitivesounding phrases that are easily memorized and easily expressed” can also be categorized as thought-stopping phrases according to psychiatrist Robert Jay Lifton (1961). These phrases include repeated (and alliterative) phrases, such as “It is what it is”, function to prevent any criticism of an ideology by signaling the end of any further analysis.

Subliminal messaging is another technique that has also been used by spin doctors in political propaganda. One of such confirmed cases is the use of the word RATS that was flashed on the political advertisement viewers’ screens for several frames when the word bureaucrats was displayed. This word had been chosen intentionally in a study conducted by Weinberger and Westen (2008). The researchers found that the subliminal “RATS” message depressed participants’ ratings of the candidate, while the other three words did not.

A newer area of research that is relevant to this discussion is call “phonological neighborhood density.”

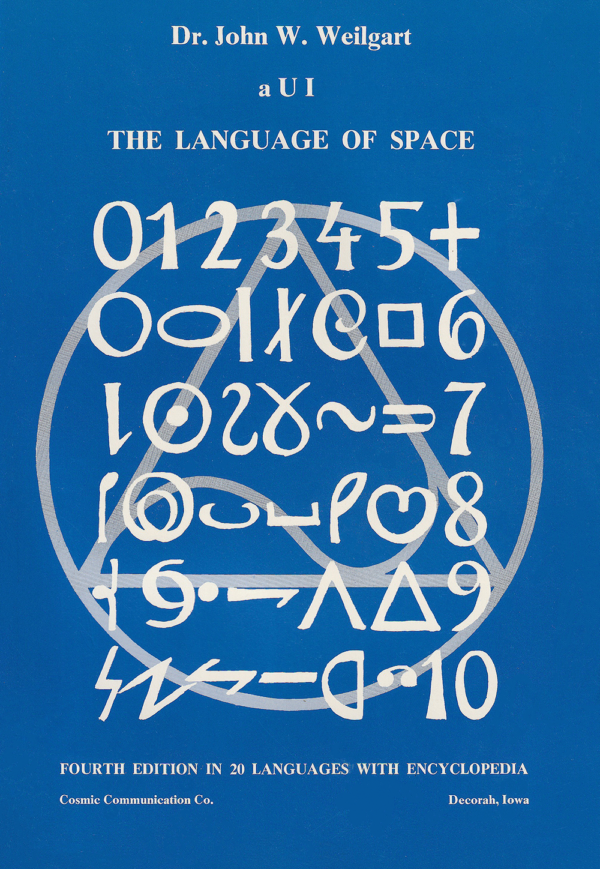

This literature review includes citations on phonological neighbourhood density which reveals the deep connection between phonological and semantic processes in our brain as well as my attempt to infer whether it can serve as a rationale for a language such as aUI having a closer connection between semantic and phonological systems, thus facilitating communication and serving both comprehension and speech production. Full references and more context will be provided if necessary.

Philipp Shary, PhD, Linguist, RUDN University

23 August 2021.

The existence of the definition of phonological neighborhood density reveals the fact that the phonetic connection between similar sounding words is widely recognized by the academia and can be described as a well-established term:

Phonological neighborhood density is the number of words that differ from a target word by the addition, subtraction, or substitution of a single sound (Landauer and Streeter,1973). For example, the word “phone” has many neighbors including “cone”, “tone”, “loan”, “own”, “foam”, etc., whereas “month” has none.

Furthermore, a substantial number of researchers (Hsin-Chin Chen, Jyotsna Vaid, David A. Boas, and Heather Bortfeld; Michele T. Diaz, Hossein Karimi, Sara B.W. Troutman, Victoria H. Gertel, Abigail L. Cosgrove, Haoyun Zhang; S. Gahl, J.F. Strand; Chen, Q., & Mirman, D.; Julie D. Anderson) have demonstrated the existence of a connection between lexical and phonemic activation:

It has been established that word processing occurs as a result of bidirectional, excitatory spreading activation within a network of semantic feature, word (lexical or lemma), and phoneme (sublexical) layers.

The following extract sheds some light on the sequence of events that takes place during speech production. Presumably, aUI might help to facilitate the process by introducing a shortcut connecting the two stages:

This increase in activation of the shared phonemes will feed back to the target word, thereby increasing its level of activation, along with the probability that it will be selected for production. The most activated word is eventually selected, ending the stage of lexical processing. The selected word is then given another boost of activation, marking the beginning of the phonological processing stage.

Higher phonological neighborhood density has a positive effect on speech production, yet might hinder perception:

Phonological neighborhood density has been shown to influence both perception and production, where larger neighborhoods often produce interference during perception and facilitation during production.

This hypothesis is also confirmed in the paragraph below:

Experiment participants are faster at making lexical decisions to words with many vs. few phonological neighbors (Yates et al., 2004).

However, some studies show a disconnect between the two processes and a higher reliability of semantic memory compared to the phonological one:

Age-related increases in retrieval difficulty may be related to phonological aspects of the stimuli. For example, older adults have more tip-of-the-tongue (TOT) experiences (Burke et al., 2004; Burke et al., 1991; Maylor, 1990; Rastle and Burke, 1996) which reflect phonological, but not semantic retrieval failure.

Additionally, there is an extract that might be viewed as a counterhypothesis to the theory of synergy between the two types of memory as it emphasizes the increase of the categorization difficulty related to the higher density:

The fact that words in dense neighborhoods tend to be difficult to recognize fits a widely held intuition: that neighborhood density effects arise because phonological neighbors tend to sound similar to one another. The more neighbors a word has, the more words it resembles, which increases the difficulty of the categorization semantic understand task faced by the listener.Finally, another short citation [TBD] underlines the facilitative effect provided by a higher phonological degree of density/similarity:

Phonological neighbors produce a facilitative effect even in spoken word recognition when semantic context weakens the activation of phonological neighbor.

References

- Dingfelder, S. F. April 2012. The science of political advertising. Monitor on Psychology, 43(4).

http://www.apa.org/monitor/2012/04/advertising - Foster, Timothy. How Ad Slogans Work.

https://money.howstuffworks.com/ad-slogan.htm - Lifton, R. L. (1961). Thought Reform and the Psychology of Totalism. Norton, NY. In

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Thought-terminating_clich%C3%A9 - Razran, G. (1939). A quantitative study of meaning by a conditioned salivary technique (semantic conditioning). Science, 90, 89-90.

- Razran, G., 1961, The observable unconscious and the inferable conscious in current Soviet psychophysiology: interoceptive conditioning, semantic conditioning, and the orienting reflex. Psych. Review 68:81-147.

- Razran, G. (1961). The observable unconscious and the inferable conscious in current Soviet psychophysiology: Interoceptive conditioning, semantic conditioning, and the orienting reflex. Psychological Review, 68, (2), 81-147.

- Schwarz, L. A. (1948, 1949). Knowledge of the word and its sound form as a conditioned stimulus. Bull. Exp. Briol. Med. 25, 292-4: 27, 412-15.

- Weinberger, J. and Westen, D. (2008). RATS, We Should Have Used Clinton: Subliminal Priming in Political Campaigns. Political Psychology. 29: 631-651.

https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9221.2008.00658 - Wikipedia.

https://www.sourcewatch.org/index.php/Alliteration - Xiaosong. Ding. Stylistic Features of the Advertising Slogan.

https://www.translationdirectory.com/article49.htm